The belief in Airbnb: the miracles of cult marketing

In the latest issue of Misset Hotel, Jeroen Oskam comments on the marketing strategy of the urban vacation rental platform Airbnb. The article summarises a chapter in his latest book on The Future of Airbnb and the “Sharing Economy”.

"Airbnb against the hotel industry?"

The Airbnb debate has taken surprising turns. Suppose a new and successful car manufacturer appears on the market. The new player faces protests because of the pollution caused by his factories; the safety of his cars are questioned and there are rumors about tax evasion. The company's only defense is: "Those are allegations of the automotive lobby!"

The example sounds absurd, but is no different from what is happening in the hotel sector: Airbnb's offer is estimated at 5.3 million units, with 164 million guest arrivals by the end of 2018. The value of the company is estimated at US$38 billion. Nevertheless, it positions itself in the discussion as a “non-company”. It has successfully framed the discussion as "Airbnb against the hotel industry". Why don’t we consider Airbnb, just like competitors Starwood and Accor, as part of the hotel industry?

This false contradiction between Airbnb and hotel companies is just one example of the marketing fabrications disproved by research. The image of the Airbnb guest and provider is based on the brand image, but not on the actual situation. Why people choose Airbnb, and not a hotel, is often unclear. There is also a wrong understanding of the impact of urban vacation rentals. The idealistic and utopian image of the platform is not just a fortuitous misinterpretation, but it was created as the result of a deliberate and highly effective marketing strategy.

The culting of brands

The Airbnb brand has surrounded itself with believers who are not very open to facts about urban vacation rentals. This strategy is well documented; in 2004 Douglas Atkin published the book The Culting of Brands: Turn Your Customers into True Believers. 10 years later —Atkin is then Global Head of Community at Airbnb — he puts these ideas into practice. He does not position Airbnb as a regular company, but as a social movement.

In his book, Atkin disputes that cult members are psychologically flawed or socially inept conformists: cults appeal to people who feel slightly different than mainstream, and who look for like-minded people. A cult goes in search of these loners, helps them differentiate themselves from the rest of the world and "demonises" the opponent. The cult offers full acknowledgement, in Atkin’s theory, to these singular individuals.

New members must be received, just as by the "Moonies" (the Unification Church) with a so-called "love bomb". They can be mobilised by demanding in increasing extent of commitment, while at the same time offering a more rewarding integration in the “cult”. In the public debate about Airbnb in San Francisco, Atkin compared the lobby meetings of the company with Obama rallies. The fanaticism of the proponents gave the impression of overwhelming social support for the urban vacation rental platform.

Living like a local

This approach also helps understand the promise of ‘Living like a local’. It would be a misunderstanding to believe that Airbnb offers its guests more connection with residents and other tourists. Innovative hotel concepts have started to invest in public spaces in order to be able to offer that community experience; the strange thing is that precisely public spaces are not part of the Airbnb offer. No lobby that invites to meet strangers, no socially skilled hotel staff: on the contrary, the Airbnb guest is free to have breakfast in his or her underwear at three o’clock in the afternoon.

If we analyse Airbnb's video campaigns, we see what ‘Living like a local’ means. The best example is the Don’t go to Paris (Live in Paris) campaign. The Airbnb guest hardly has more contact with the host than the traditional hotel guest with a receptionist. He is also not looking for the “other face” of Paris, but simply wants a view of the Eiffel Tower. He does have more contact with his own travel company. And, the most important difference: he does not feel obliged to behave as a typical tourist who visits tourist highlights, but can simply fall asleep on the couch.

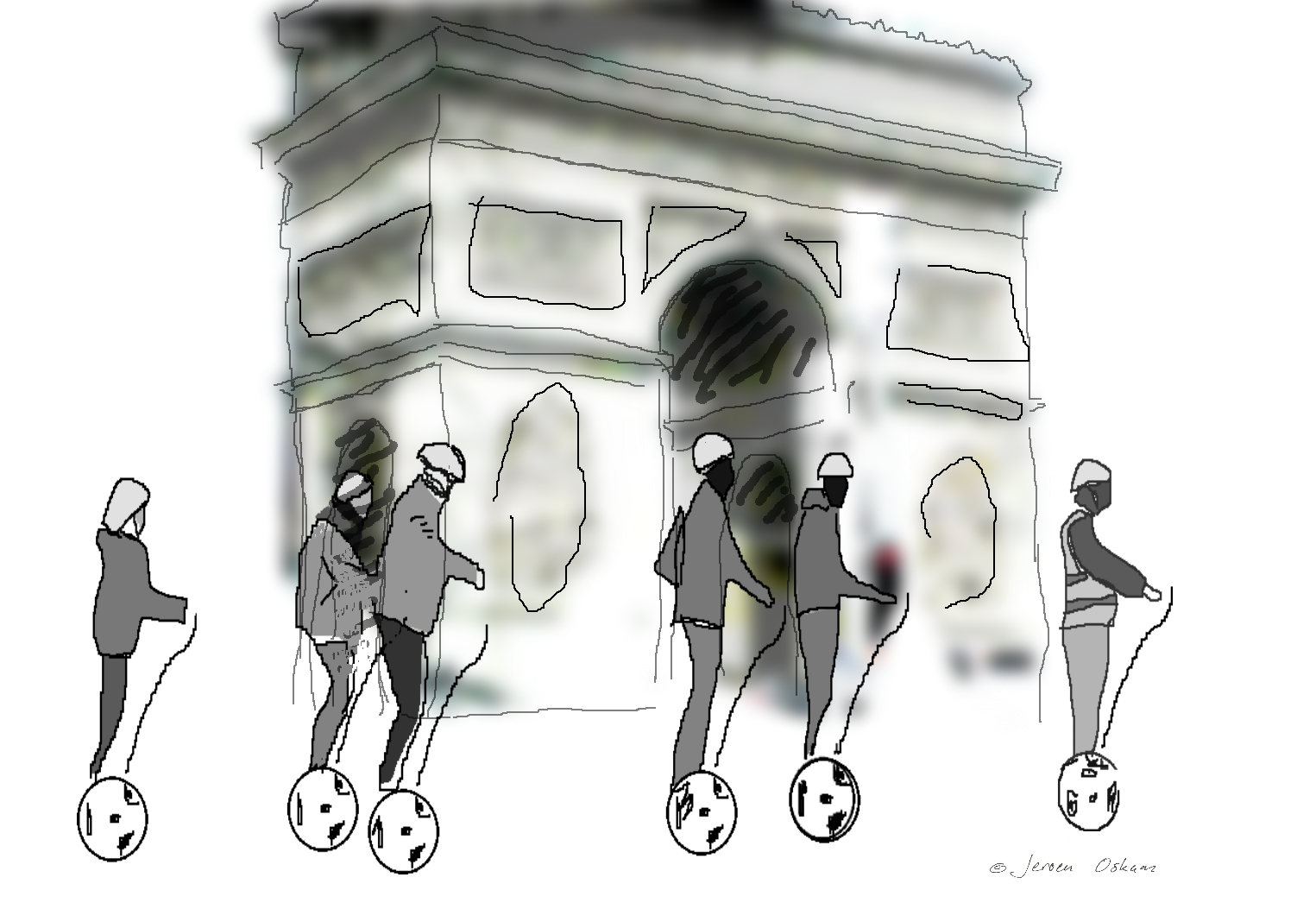

Those who do not use Airbnb, the campaign suggests, are forced to that unspontaneous type of behaviour: images of tourists on Segways in front of the Arc de Triomphe "demonise" the herd behaviour of the mass tourist. The Airbnb guest does not consider him or herself to be a tourist, an image with which traditional hotels can impossibly compete. Ironically, there were 1.4 million visitors in Amsterdam in 2017 who believed they were not mass tourists.

The majority of Airbnb guests makes his or her choice because of the tangible benefits: lower price, more square meters. The target group are not necessarily hipsters or millenials: the offer of city apartments is especially attractive for families. Urban vacation rentals thrive because of a new trend: who went to a city trip twenty years ago with children?

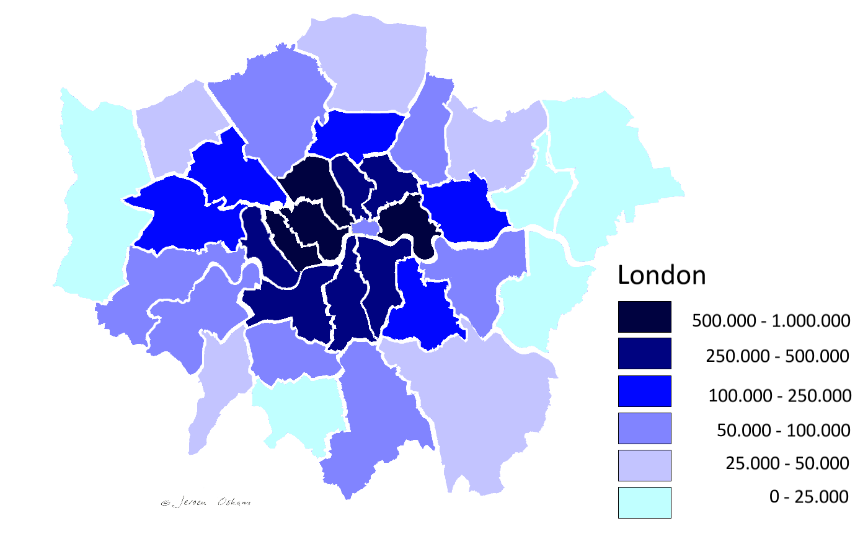

Once in the city, the Airbnb guest behaves similarly to the traditional tourist. Unlike what many people (and city authorities) think, Airbnb therefore does not contribute to the spreading of tourism. On the contrary: the supply is more concentrated in the city centres than traditional hotels. To be precise: in Amsterdam we find 51% fewer Airbnbs per kilometer distance from the central Leidseplein. Airbnb units are on average 7.4% cheaper per kilometer and get 0.6 nights less booked. This concentration pattern can be found in all European cities:

Convergence

The biggest strategic challenge for Airbnb is to increase its market share in the business segment. That requires a consistent service, something that seems incompatible with the image of a surprising offer that is different everywhere. Therefore, we expect a "convergence" to occur between urban vacation rentals and traditional hotels: the difference is getting blurred. Due to market growth, the Airbnb guest and his or her expectations are changing. Airbnb is also redefining its strategy. An increasing push for standardisation leads to disappointment of the early Airbnb hosts: instant booking suppresses their control and the communication with the guest prior to their booking. During the stay, the guest increasingly assumes that the host acts as a hotel employee, and politely merges in the background.

We foresee that this "convergence" will further continue. Airbnb will evolve ever more as a traditional hotel business, and as soon as the uncertain factors are removed from the regulatory debate, mainstream companies will further invest in vacation rentals. That implies that the players in this market will be changing. Already, vacation rental revenues by Booking are comparable to those by Airbnb. We also consider the so-called “Napster scenario”, in which the Airbnb company and the brand disappear due to scandals or legal issues, but in which the market is taken over by established companies.

Conclusion

Airbnb has successfully positioned itself as an "anti-hotel company" because of what one of its executives has described as cult marketing. The cult followers establish a belief in features of the company that are invalidated by facts and research. Airbnb never replies to such research or to any other critical comments; critics of the company — whether they are the tenants' associations in San Francisco, the left-wing city council of Barcelona or researchers from our school — are denounced ad hominem as participants in an international conspiracy by a hotel industry lobby. However, due to "convergence" with the traditional hotel sector, this anti-hotel narrative will increasingly lose power in the future.

See also: Douglas Atkin, The culting of brands. Turn Your Customers into True Believers. New York: Portfolio, 2005. ISBN 978-1591840961.

Jeroen Oskam, The Future of Airbnb and the "Sharing Economy". The Collaborative Consumption of our Cities. Bristol: Channelview, 2019. ISBN 978-1845416720.