Centripetal demand in Airbnb

Airbnb was founded in 2008 and was initially considered to be an alternative way of travelling, especially appealing to travelers with an anti-consumerist lifestyle who were looking for “off the beaten track” experiences. It would allow people to discover real city-life, as they would no longer stay in hotels in overcrowded city centres, but among the residents of the city in their neighbourhoods. Airbnb was thought of in a way as “Couchsurfing 2.0”, not only in popular media but also by politicians and by scholars in hospitality and tourism.

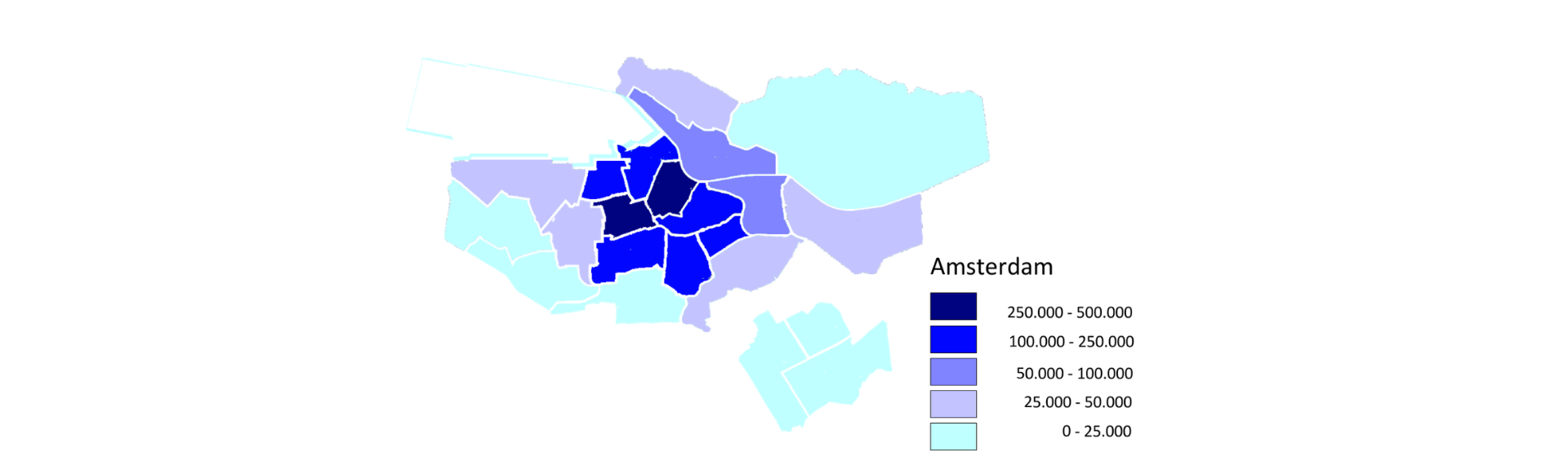

When Hotelschool The Hague researchers started analyzing Airbnb data, they found a reality that was totally different. The two most striking differences with the idealist image of Airbnb were that, instead of ordinary people making ends meet, commercial businesses owning or operating numerous apartments were found; and that Airbnb was increasingly concentrated in city centres.

This was a troubling finding: since 2015, residents of Amsterdam and other cities had become concerned with increasing tourist crowds, and with the changes this trend was causing for e.g. the kind of shops and other services they could find. Whilst in the idealist interpretation Airbnb could be a remedy against this so-called ‘overtourism’, could it in reality be part of the disease?

Our findings were confirmed by papers about Airbnb development in some other cities. With the amount of data that had been collected in our research during the past few years, we were now able to make an analysis of 26 European cities, and see if this central concentration was a common pattern, or whether it was just a matter of chance that in the cities we had looked at we observed that effect.

Our study found that there is indeed a very clear and strong concentration in most cities. Not only the number of Airbnb units increases exponentially when we come closer to the city centre, but also Airbnb prices and are higher, as well as the number of bookings. This indicates a demand effect: people may try to offer an Airbnb apartment anywhere, but tourists, also the Airbnb ones, prefer city centres. Only two cities showed a somewhat different pattern: Bruges and The Hague. What these two exceptions have in common is that they have an inland centre and a secondary centre closer to the coast, which is also popular with tourists.

What does this mean? In the first place, that Airbnb guests are tourists like any other. This is important, because “authenticity” is often seen as the driver of Airbnb growth, but that appears to be very relative. As argued elsewhere, Airbnb travelers are not looking for the authentic city and its residents; they are looking for their authentic selves, and do not want to be considered as tourists. The finding also has policy implications. A few years ago, some cities still embraced Airbnb as a way of spreading tourism and reducing congestion. Nowadays, in part thanks to the research conducted by Hotelschool The Hague, this illusion seems to have been abandoned.

The article “Eiffel Tower and Big Ben, or ‘off the beaten track’? Centripetal demand in Airbnb” was published in Hospitality & Society, 10(2), 127–55.